Finished reading: Legends & Lattes by Travis Baldree 📚

Finished reading: Legends & Lattes by Travis Baldree 📚

I read 75 books in 2023, my high water mark for the most reading in a year. Books have always been like a warm blanket, and I needed that comfort during a most challenging year.

You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. — James Baldwin

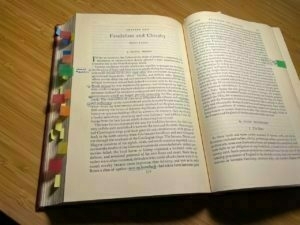

I took on some ambitious books during the year. I read Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, which has long been on my to-be-read pile. I read a new translation of The Odyssey after having last followed the plight of heroic Odysseus some thirty years ago. I am tackling a multi-year reading of Will and Ariel Durant’s epic eleven-volume Story of Civilization. I inherited these books from my Grandmother twenty-five years ago, and I have finally found the time to read them. Discovering her careful handwriting in the margins of these books has revealed a new and somewhat startling side to my prim and proper Grandmother. What you mark and highlight says a lot about your thoughts and beliefs. It’s like a second history is being told in these pages. I’ve decided to leave my own trail of marginalia for my daughter, should she find the patience and fortitude to complete this generational journey herself one day.

A Slow Read of The Story of Civilization

A Slow Read of The Story of Civilization

Finished reading: Wednesday’s Child by Yiyun Li 📚

My 75th book of 2023, which is a new personal record for the most books I’ve read in a single year. Many of the stories in this collection touch on the hard to articulate grief of losing a child, which hit home for me. ★★★★☆

Currently reading: An Immense World: How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us by Ed Yong 📚

Finished reading: Holly by Stephen King 📚

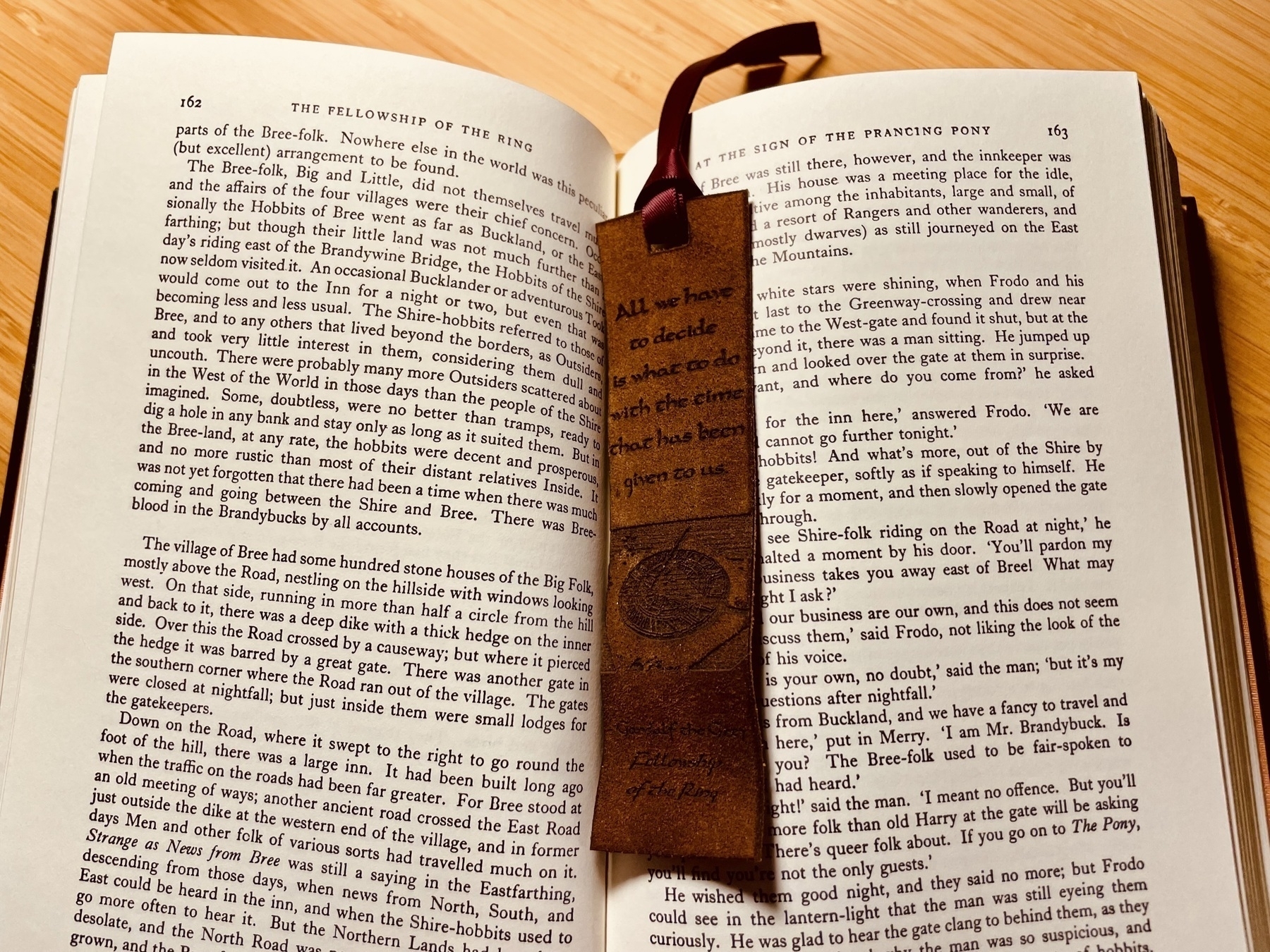

I found this lovely bookmark in my Christmas stocking. Santa knows me so well! 📚

Finished reading: The Private Library by Reid Byers 📚

Book-wrapt — that beneficient feeling of being wholly imbooked, beshelved, inlibriated, circumvolumed, peribibliated … it implies the traditional library wrapped in shelves of books, and the condition of rapt attention to a particular volume, and the rapture of of being transported to the wood beyond the world.

… and

Entering our library should feel like easing into a hot tub, strolling into a magic store, emerging into the orchestra pit, or entering a chamber of curiosities, the club, the circus, our cabin on an outbound yacht, the house of an old friend. It is a setting forth, and it is a coming back to center. Borges, of course, thought it was entering Paradise.

Sometimes a book feels like it was written just for you. May we all find ourselves Book-wrapt this holiday season. ★★★★★

Currently reading: Holly by Stephen King 📚

Finished reading: Writing Tools by Roy Peter Clark 📚

A slow read over the course of a few months, one chapter/writing tool per sitting. Lots of great tips and advice to improve your writing.

Finished reading: The Book on the Taboo Against Knowing Who You Are by Alan W. Watts 📚

Another compelling argument for being present in our lives, and paying close attention to the marvels that surround us.

How is it possible that a being with such sensitive jewels as the eyes, such enchanted musical instruments as the ears, and such a fabulous arabesque of nerves as the brain can experience itself as anything less than a god?

Currently reading: Wednesday’s Child by Yiyun Li 📚

Finished reading: The Vagabond’s Way by Rolf Potts 📚

Finished reading: Christine and Blaze by Stephen King 📚

Continuing my quest to read the Stephen King books I missed along the way. With these two, I’ve now read thirteen King books this year. The 700-page Christine book flew by on my Kindle. Lots of supernatural fun mixed in with nostalgia for my late 1970s youth. I’m tempted now to watch the movie, which I somehow also missed.

I listened to the audiobook version of Blaze on long walks through the Arizona desert. I enjoyed the story with just a hint of the otherworldly, feeling sorry for the misunderstood and troubled Blaze.

Right now, I have just fifteen more books to go, until this prolific author publishes his next one. It feels a little like walking up the down escalator. But what a great problem to have.

Finished reading: The Age of Faith by Will Durant 📚 I finished this fourth installment of Will Durant’s Story of Civilization after three months of slow, careful reading. The Age of Faith begins with the fall of Rome and carries through the end of the Middle Ages. The writing is clear, colorful, engaging, often horrifying, and occasionally laugh-out-loud hilarious. Along the way, I encountered kings and popes, treachery and atrocities, saints and philosophers, economic systems, the building of cathedrals and castles, and primers on the great works of literature and philosophy across a thousand years of recorded time.

Finished reading: Your Brain on Art by Susan Magsamen and Ivy Ross 📚

Your Brain on Art is the latest selection from the Next Big Idea Club. The authors did a nice job of gathering scientific evidence of how art making and appreciation physically changes your brain. I loved the part where a scientist discovered that different sound waves can alter the shape and appearance of our heart cells. Lots of good science-based tips on how to flourish by incorporating art in your everyday life. For me, I’m planning to spend more time really listening (and dancing!) to new music, not just having it on in the background. ★★★★

Finished reading: The Art of Living: Peace and Freedom in the Here and Now by Thich Nhat Hanh 📚

Impermanence is something wonderful. If things were not impermanent, life would not be possible. A seed could never become a plant of corn; the child couldn’t grow into a young adult; there could never be healing and transformation; we could never realize our dreams.

Sometimes the universe sends you exactly the book you most needed to read. What a clear-eyed and compelling manifesto of living your best life right now. ★★★★★

Currently reading: The Art of Living: Peace and Freedom in the Here and Now by Thich Nhat Hanh 📚

Finished reading: The Eyes of the Dragon by Stephen King 📚

Continuing my quest to go back and read the Stephen King books I’ve missed along the way. I listened to the audiobook of this one, narrated by actor Bronson Pinchot. I’ve listened to hundreds of audiobooks, but the narration of the ending of this story was one of the most incredible I’ve ever had the pleasure to hear. Bravo! ★★★★

Finished reading: The Silentiary by Antonio Di Benedetto 📚

What a strange little book. The narrator is slowly driven insane by all the commercial sounds encroaching on his family home: an auto repair shop next door, a nightclub across the street, an idling bus outside his bedroom window, all told in disjointed Kafka-like stream of consciousness. Made me appreciate the relative quiet I enjoy here at home. ★★★

Started reading: Your Brain on Art by Susan Magsamen 📚