Writing Things Down in a Paperless World

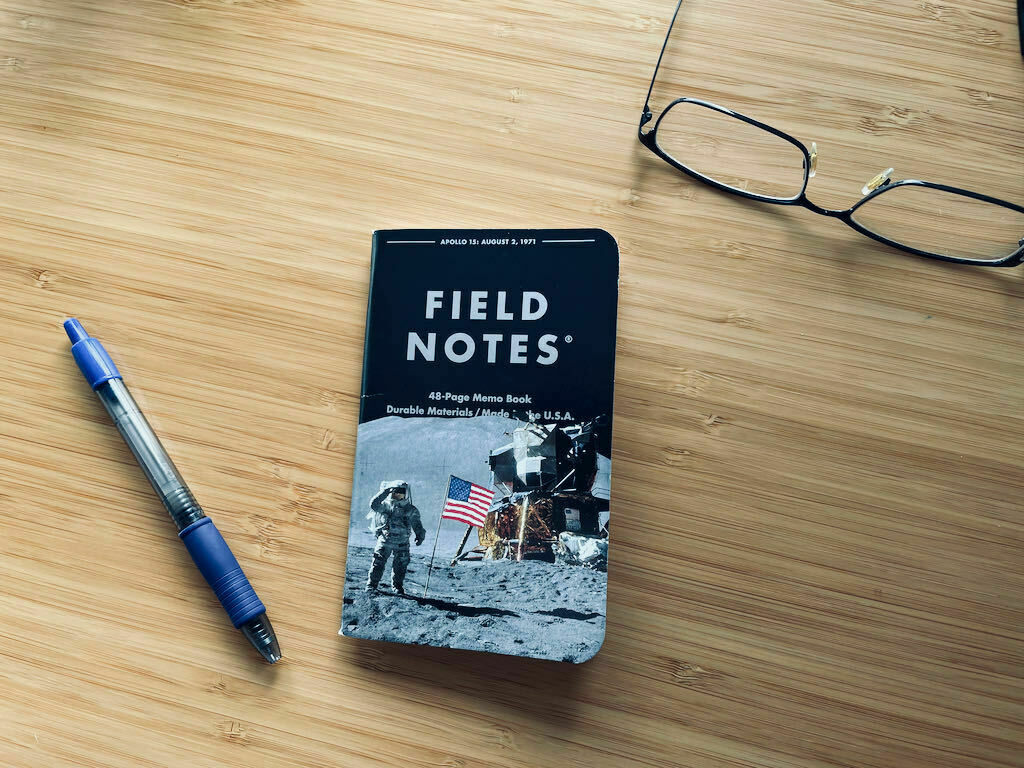

For the past ten years, I have been on a mission to eradicate paper from my work and home life. I can now access information more quickly and from anywhere, whether at sea or at the Apple Store where I need to produce the invoice for a dead MacBook Pro. And yet, one hold-out refuses to go gently into that dark night of paper annihilation: my Field Notes notebooks. These pint-sized memo books with their quirky designs and durable paper still travel with me just about everywhere. I sometimes wonder at the irony of using a $1,000 iPad Pro as a lap desk to scribble in a $4 notebook.

With everything else in my life so digitally focused, why do I still fill one of these 48-page Field Notes every three or four weeks?

This morning, I pulled out a year’s worth of tattered notebooks to see if I could solve this mystery. To be honest, I was apprehensive at looking too closely. Part of me wanted to leave well enough alone and not probe, perhaps fearing that I would find a bunch of meaningless jibber-jabber and force myself to give up these little books that I love so much. With some trepidation then, I skimmed the scribbles, diagrams, lists, weird dreams, single underlined words, whole paragraphs of intense, slanted scrawl, arrows, and lots of scratched-out words. Each notebook told a confused story about my state of mind at the time: hopes and worries, looming decisions, crazy, half-baked ideas, and incomplete solutions to problems that troubled me. As I flipped the pages, I watched meandering thoughts morph and solidify under the pressure of continued probing and analysis.

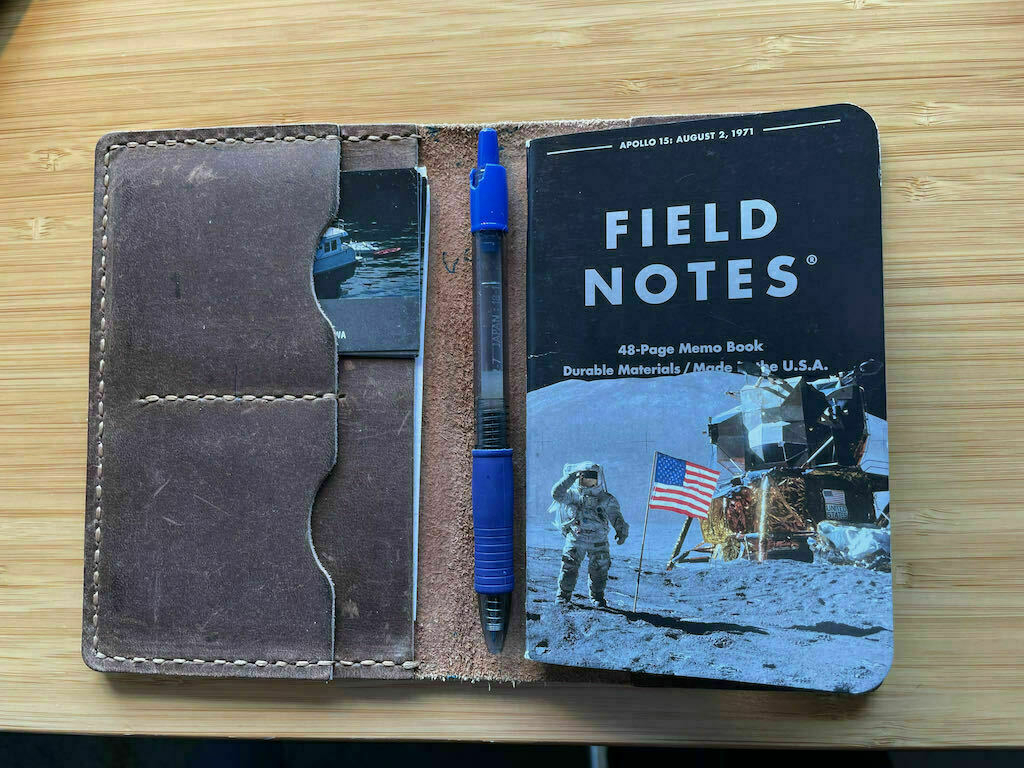

Give me a small canvas of blank paper and a pen, and I can slip into a deeper mental state than I seem to achieve in front of a blinking cursor. After a few minutes of doodles, I may even open a tiny crack into my subconscious. The physical act of handwriting may provide a familiar comfort that allows my mind to settle and focus. Perhaps it’s the simplicity of the interface: no buttons, no battery to charge, just me and my ill-formed thoughts. Maybe the old leather cover I use to carry the notebook and pen, scuffed and softened over many years of use, sends a chemical signal through my fingertips to open, to relent.

Psychologists have shown that writing things down on paper helps you remember better. The folks at Field Notes understand this:

Jamie Rubin, a writer and technology enthusiast, recently returned to notecards for his reading notes after struggling to reap the benefits he expected from keeping these inside Obsidian. I store my reading notes in Craft but have encountered few of the promised eureka moments since adopting this Zettelkasten technique of hyper-linked notes. While I appreciate the ability to retrieve and update these notes quickly, I don’t seem to be able to think as clearly (or as abstractly) within an app like Craft as I do on paper.

In one of Nabokov’s lectures on literature 1, he defines memory as one of the four key attributes of a good reader (or thinker). Whether you remember things by writing them down or searching your Obsidian vault might be a wash. He calls having a nearby dictionary the second important attribute. Here, I tip my hat to the internet. How satisfying it is to tap an unknown word on the screen of a Kindle with my finger, and as if by magic, a well-crafted definition (or translation, or Wikipedia page) appears without leaving my place in the text. But, it’s his final two attributes of a good reader, that of having an active imagination and some artistic sense, that strike me as the hardest to achieve digitally. Artistry and imagination are still the dominion of pad and paper.

When I’m stuck on something, I instinctively reach for my little notebook — not my iPad. And while what I capture is often raw and disjointed, I review these notes every morning over coffee, checking in with my subconscious, allowing fragments to inch together as if by magnetic pull. It might take days or even weeks of scribbles and circled words to reach true clarity of thought.

When Jimmy Buffett has an idea for a song — sometimes just a phrase — he writes it down on any available scrap of paper and stuffs it into an old sea chest. When he’s ready to write some new music, he sits down and pulls out all those scribbles, which I imagine must be torn off bar napkins and beer coasters, and sorts through them, one by one. He says many of his most popular songs marinated in his sea chest before emerging as lyrics.

I do something similar in Field Notes. I reserve the last page of every notebook for my “Compost Heap,” a technique I borrowed from Neil Gaiman’s wonderful MasterClass on storytelling. Here, I write down bizarre images from dreams, lines from songs, evocative phrases, short descriptions of people I’ve met, places I’ve visited — really anything. Over a few weeks, the list grows to a page or two of disconnected images and ideas, and often, I discover a larger mosaic than my conscious mind could articulate on its own.

The whimsy of Field Notes encourages this kind of abstraction. These little books would be plenty happy to record Scrabble scores or grocery lists or meeting notes. I’ve used beautiful leather-bound journals in the past and felt that unease at despoiling that first cream-colored, thick-stock blank page. Something fancy like that would freeze me in my tracks. But a wee Field Notes notebook urges me to scribble thoughts that haven’t left that gauzy symbolic state in my mind or bump together two very different lines of thinking whose offspring becomes a new insight.

Don’t get me wrong: a computer is terrific for capturing, storing and retrieving transactional or reference information. I would never go back to the stacks of files and paper that once littered my office. And while I love the promise of technology helping me uncover new insights and connections, I have come to accept — and celebrate — that my best thinking still takes place within the humble confines of a pen and a Field Notes notebook.

- Vladimir Nabokov, Lectures on Literature (A Harvest Book, 1980), 32. ↩