The Cost of Indiscretion

As a licensed CPA and long-time boat owner, I’m no stranger to the financial consequences of keeping a boat. People like to joke about how quickly money flows into a boat, like stuffing $100 bills down a bottomless drain. Or, how many “boat units” a particular upgrade or repair will be. Somehow, six boat units sound better than $6,000.

When we were shopping for our trawler, our yacht broker shared this financial rule of thumb: expect to spend about 10% of the value of the boat each year on maintenance, upkeep, moorage, and other ownership costs like insurance, taxes and fees. The rule worked on our $70,000 sailboat. We spent about $7,000 a year on boat-related costs. But surely, that math couldn’t extend to a $700,000 trawler. Could it?

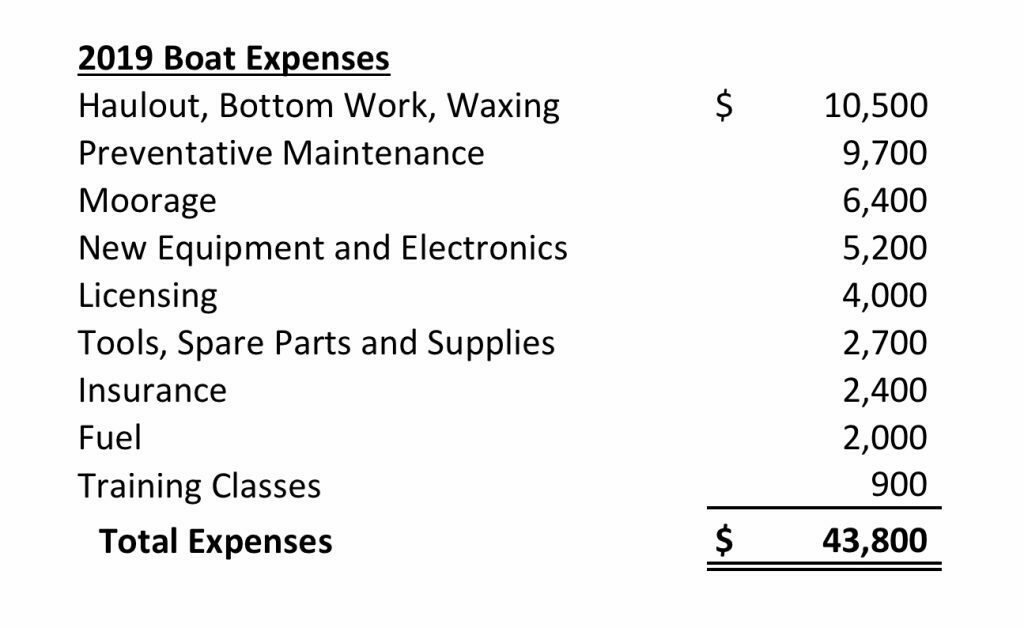

Here’s a summary of last year’s costs for Indiscretion. We spent roughly $44,000, a small fortune for us frugal sailors, but “just” 6% of the boat’s value. Here’s where the money went:

Two insights to share upfront. First, fuel costs of operating a full-displacement trawler are usually low on the list of expenses. We took on fuel just once in 2019. This was a positive surprise as we entered the world of these efficient yachts. Second, since owning Indiscretion, we’ve incurred almost no costs for equipment or mechanical failures. Everything we’ve spent has been either upgrades or preventative maintenance to avoid costly repairs in exotic locations — also a positive surprise.

About half our annual expense came in one fell swoop during our haul-out at Canal Boatyard in Ballard. Oomph! We outsourced the work to a marine contractor since we had some specific deferred maintenance tasks we needed to tackle. In our case, overdue seal replacements for our stabilizer system and a reconfiguration of our electrical panel, which totaled about $7,500. The balance of the costs hit us like slashing knife wounds: $1,500 to drain and replace engine coolant, $2,000 to update our electronics software and charts, $6,000 for bottom sanding and painting, $2,500 for yard fees and haul-out, $1,000 for hull waxing, $1,000 for assistance with transiting the Ballard Locks, and $1,600 for a sundry of supplies and other charges incurred during the haul-out.

Once the initial shock wore off, I took a more philosophical view of these expenses. Some of the bigger ticket costs were expert upgrades or infrequent maintenance tasks that won’t repeat each year. A complete bottom sanding and painting can last two or three years. And the thousands we spent on tasks like changing the engine coolant or help with moving the boat, I will undoubtedly do in the future. However, I am sure I will need other upgrades or expert assistance in the future. For example, this year, we employed an electrical contractor to replace Indiscretion’s battery charging system to make our generator time at anchor more efficient. And sooner or later, I will need to pull out the boat’s aging muffler system and replace it with a new one. After reading about the replacement experience on a sistership’s blog, I quickly concluded that this is a job best left for professionals.

Lessons Learned from Employing Marine Contractors

I learned some lessons about the use of marine contractors during our two years of trawler ownership. First, there are some amazingly talented marine technicians who can perform near-miraculous repairs and upgrades to yachts based on their years of experience and inside knowledge. Second, they operate like any business and thus are, of course, incentivized to maximize their revenue. This might mean replacing equipment that could be repaired more economically or undertaking work that isn’t necessarily warranted. Third, anything I outsource to a contractor that I might need to do in the future to maintain the safety of the boat is a lost learning opportunity to advance my mechanical skills.

Here’s a prime example of a case where the contractor’s business model conflicted with my best interests: shortly after purchasing Indiscretion, I noticed a small amount of oil in the engine room flowing from our wing engine. I examined the engine, but I could not locate the source of the leak. It wasn’t a lot of oil, but after cleaning the bilge, more would soon appear, even if I hadn’t operated the engine. Our contractor diagnosed the problem and recommended we replace the wing engine’s transmission. The job would take a couple of weeks and cost $6,000. We learned all this at the beginning of summer, and since the transmission worked fine, and we weren’t losing any oil in either the engine or transmission, I deferred the job until the offseason. During our summer cruising, the leak stopped altogether and hasn’t reappeared. I now suspect that the oil resulted from a spill during an oil filter change. We clearly didn’t need to replace the transmission.

I've learned to limit my use of marine contractors to projects that meet these three criteria: (1) it’s a difficult task that I wouldn’t be able to do without investing a lot of time and money in tools; (2) there is a specific scope and agreed-upon cost estimate for the project upfront; and (3), I’m able to participate in the work, so I continue to develop my skills as a fledgling trawler mechanic.

I thought last year might have been an anomaly, and our costs might drop in 2020. After all, we took a much more hands-on approach during our annual haul-out and had gotten many of the upfront costs of tools and spares behind us. But, alas no. Our boat costs this year will come in around $45,000, slightly higher than in 2019.

First Mate Lisa scraping barnacles off the keel cooler

First Mate Lisa scraping barnacles off the keel cooler

So, while our annual boating costs have come in below the 10% threshold, I still think it’s a good rule of thumb. So far, our voyaging has been limited to the Northwest, but our plans include open ocean travel and thousands of nautical miles under our keel. Insurance costs will rise, along with fuel, marina fees, weather routing, and other unforeseen costs. And If you count the 10% Washington state sales tax we paid on the purchase of the boat, and the 10% brokerage fee we’ll pay on sale, our annual costs need to stay under 6% each year to avoid exceeding the 10% rule-of-thumb over our planned ownership of Indiscretion.

Few buy boats for the financial return, but it’s smart to be realistic when planning your finances as a boat owner. None of these costs has come at a surprise to us, thankfully. We used the 10% rule as a budgeting guide going in, and these high expected operating costs in part informed our chosen name for our trawler: Indiscretion. What kind of CPA would buy an asset that not only depreciates but requires additional cash each year just to keep it running? This one did, and I have absolutely no regrets. After all, you can’t put a price tag on dreams. Just remember to keep the boat kitty full. And make sure to translate any big-ticket items into boat units when discussing costs with your first mate. It really does sound better.

If you’re a trawler owner, do you subscribe to the ten-percent rule? If not, how have you managed to keep costs low? Share your feedback in the comment section below.