The Wastelands

Grieving the loss of a child is a journey through wastelands you never expected to cross. Unlike every other challenge you’ve ever faced, there is no easy way through a loss like this. You stumble and fall. You curse. You are hobbled and bloody. You are not sure of the way. You might be going in circles.

The truth is everyone suffers in this life. It’s our lot to take the awful with the beautiful. We all must face it. In a perfect world, your mom wouldn’t forget you in the fog of Alzheimer’s Disease. You wouldn’t lose a dear friend to cancer in the prime of her life. Your son wouldn’t die in a motorcycle accident before his twenty-first birthday.

In the months before we lost Connor, we crossed a high wire of reinvention. We retired from our careers. We sold our long-time family home and said goodbye to a lifetime of friends on Vashon Island. We bought a winter home in Arizona with the half-sane plan of living a life split between the summer sea and the winter desert. For half the year, home was where we'd drop the anchor.

Reinvention might come easier for some. I felt like a reluctant hermit crab who knows he must shift to a new shell to survive but dreads the transfer. The plans were years in the making. And just at that vulnerable juncture between one shell and the other, that final letting go of the safety and security of the familiar for the heady promise of a new life, a tsunami upends everything, stranding this naked, scared crab, its tiny claws raised as if to fight the wind and water and waves.

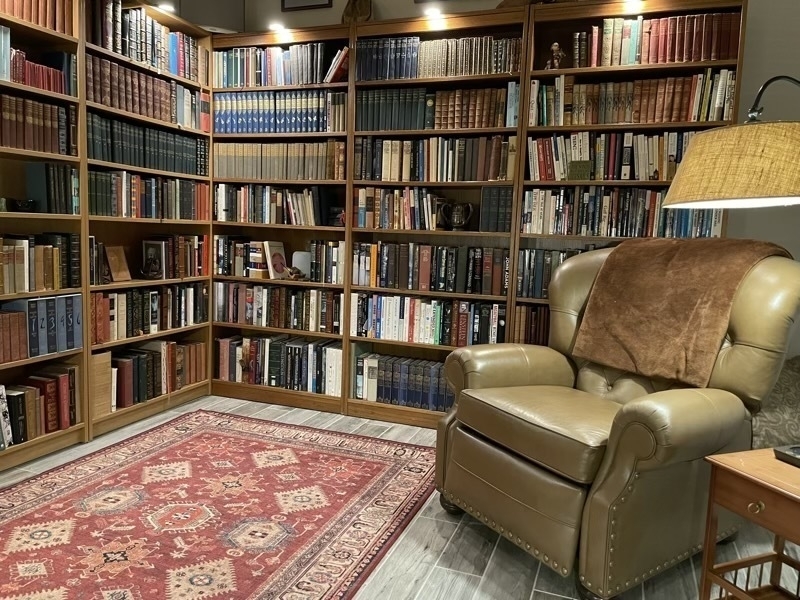

And yet, life continues. We settled into the new house in Arizona. Little bursts of joy came from unexpected sources: the convenience of curbside trash and recycling, reliable high-speed internet, and kind, welcoming neighbors. I unpacked the sixty boxes of books that make up my library, caressing each volume, inhaling its scent, remembering its message as I slowly rebuilt my sanctuary, my illusive shell.

Reading has always been a solace. I read a lot of history and philosophy these past months: the marvels of early Egypt and the brutality of Ancient Rome in Will Durant’s grand opus, The Story of Civilization; the millions of years of Earth’s geology poetically taught in Basin and Range by John McPhee; and the insignificance of our human existence in a careening, infinite universe in Probable Impossibilities by Alan Lightman. Taking a dispassionate view can ease the sting of personal loss.

We sold MV Indiscretion this spring, saying goodbye to trawler life and our ties to the Pacific Northwest. I have let go of so many layers of my identity — business professional, islander, sailor, son to my parents, and now father to my son — that it felt right to reach back to utter beginnings, where I might remake myself, like Gandalf after his plunge from the Bridge of Moria.

We bought a small off-road capable RV in April and have taken a few trips to explore the deserts and mountains of the Southwest. In June, we crossed into Mexico to camp on the shores of the Sea of Cortez. These months in the desert were the longest I’ve strayed from the ocean in my entire life. I missed the smell of the sea and the feel of dried salt on my skin. We waded in the warm surf, feeling once again that indescribable joy of shifting sand under our heels and between our toes while flocks of pelicans dove for their dinner a few yards from us.

I sat beside tide pools nestled within the rocky outcrops that lay between long stretches of sand: hermit crabs battling to defend their territories, starfish, sea stars, sea slugs, mussels, sea urchins, and tiny brine shrimp, all pursuing the minutiae of their daily lives. Looking up into the cosmos and down into a tide pool, I noted the parallels: we are all one.

A strong south wind picked up one night, and gusts gently rocked the RV on its suspension. I emerged from a heavy sleep to check the anchor, trying to remember how far we were from the rocks on shore. I drifted back to sleep, still dreaming we were afloat. I know the sea beckons on the far side of this wilderness.

After a long period of intentional isolation, I have begun the process of reconnecting with old friends and making new friends here in Arizona. This has been difficult for me. They ask me how I’m doing. Am I OK? I don’t have an answer. “What saves a man is to take a step. Then another step,” said Antoine de Saint-Exupery. Every day, I take a step.

I’m writing this tonight from a small campground in southern Colorado. We’ve been traveling for a few weeks, taking the backroads, stopping often, seeing where the open road takes us. We have no plan, no definite time to return. It feels good to roam.

Driving through western New Mexico, I felt a lightness I didn’t expect. The beauty of the colorful mesas and buttes rising around us filled me with awe. We hiked to La Ventana Natural Arch to find ourselves in an ancient, sacred place — a place of prayer and hope and resilience. It left me wanting to see more, to do more. For the first time in many months, my mind tilted forward, a blessed release from so much focus on the past.

Every day brings a little more joy and a little less sadness. On good days, I see a brightening just over the horizon. A clearing? Yet there are still those days when I sink deep into sorrow and recognize the false dawn. There is no way around this, only forward, across this barren terrain. One step. Then another. When I dare look around, I see so many others walking beside me. Grief is the price we all pay for love. Won’t you take my hand? It won’t be long now. If death has taught me anything, it's that nothing persists, not even grief.